|

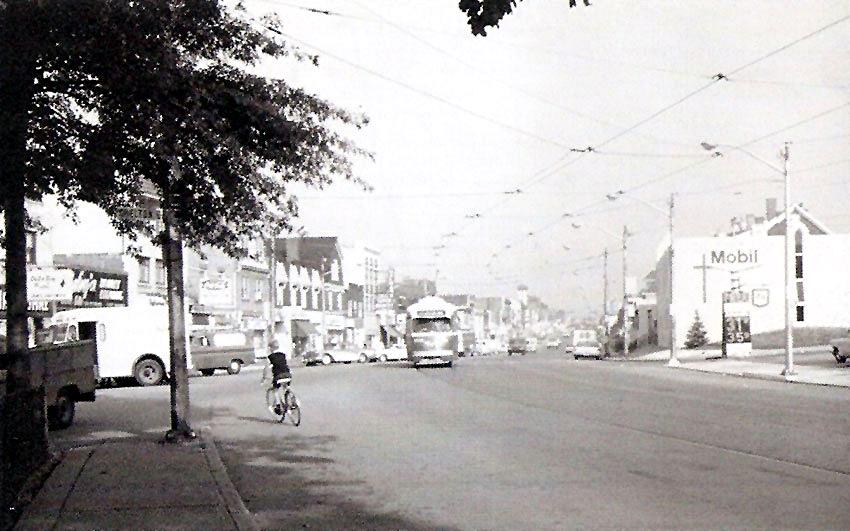

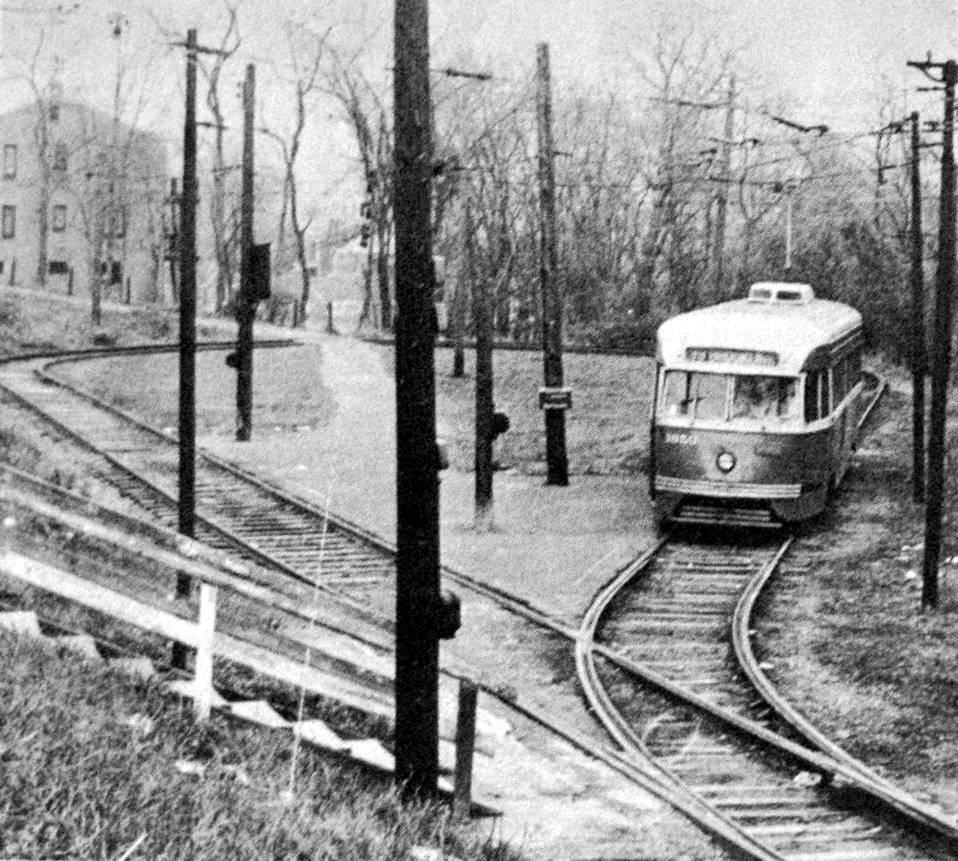

An outbound 39-Brookline moves along the

700-block of Brookline Boulevard, approaching the Flatbush Avenue Car Stop.

The History

Of Streetcar Service In Brookline

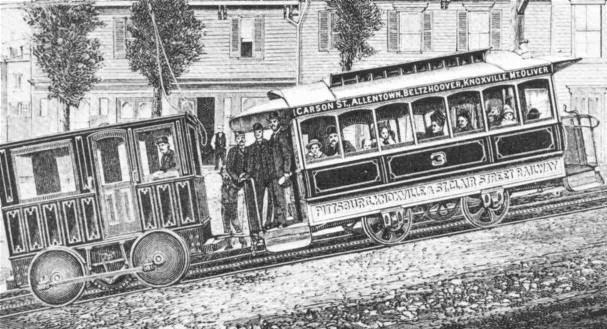

Streetcar service in Pittsburgh dates

back to the mid-1800s, when horses pulled cars along rails that ran through

some of the city's busier districts. There was a cable car service that ran

along Warrington Avenue, serving the Allentown, Knoxville, Beltzhoover and

Mount Oliver neighborhoods as early as 1859. Cable lines were in service

throughout Pittsburgh until 1897.

In the 1890s, electrified service began

in downtown Pittsburgh. Soon, there were over one hundred separate trolley

companies running within the city limits. These independent operators merged

into larger traction companies in the mid-1890s. Pennsylvania's Focht-Emery

Bill of 1901 led to a major expansion of the network and the creation of

the Pittsburgh Railways Company formed in 1902 as a consolidation of most

traction companies within the city.

♦ 39-Brookline Photo Gallery ♦

* Last Updated -

September 14, 2024 *

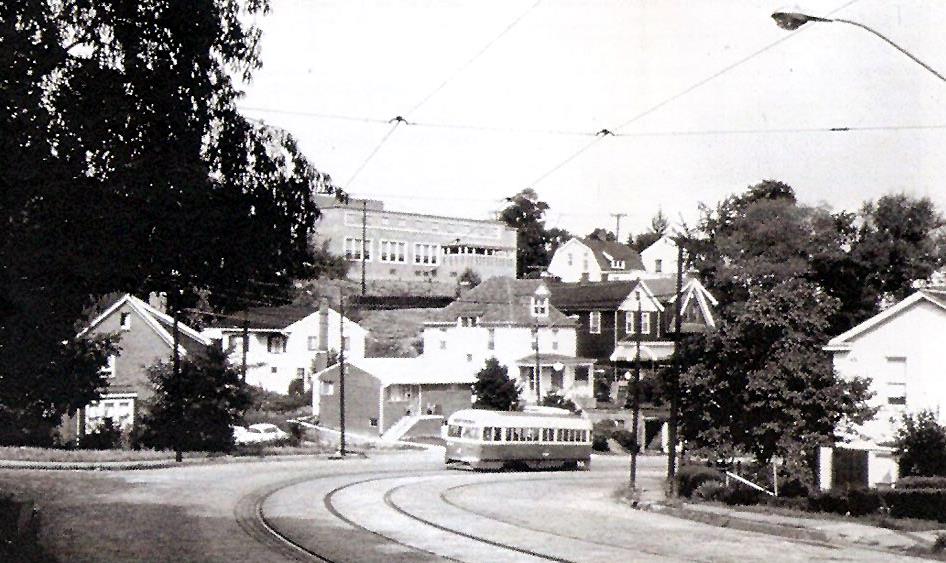

An outbound 39-Brookline at Cape

May Avenue heading south along West Liberty in May 1966.

South Hills Transportation

- The Early Years

Through the late-1800s, travel from

the South Hills boroughs to Pittsburgh, mostly farmers taking their products

to market, was a long and arduous journey over dirt roads that scaled what

seemed like mountains. The trip over Mount Washington alone could take over

an hour.

Beginning in the 1870s, an alternative

for some travelers was a ride on the passenger cars pulled by the narrow-gauge

steam locomotives of the Pittsburgh and Castle Shannon

Railroad, which

offered passenger and freight service from 1871 to 1912.

Boarding stations at Glenbury, Whited and

Edgebrook streets provided access to Brookliners. The train took travelers as far

as Warrington Avenue, where they transfered to a pair of inclines that scaled

Mount Washington to reach Carson Street. The Castle Shannon South and Castle Shannon No. 1, once in operation, also offered considerable

convenience for South Hills wagon, freight and pedestrian traffic.

A Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon Railroad train runs

through Fairhaven in nearby Overbrook.

Focht-Emery Transit Bills

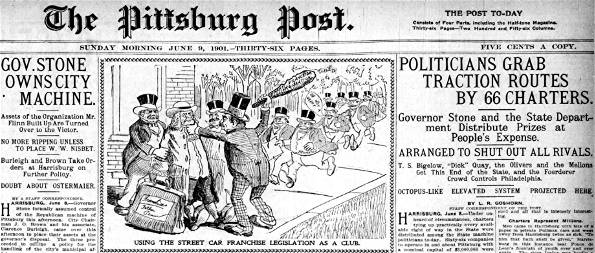

Pennsylvania's Focht-Emery Bills were signed

into law by Governor William A. Stone on June 7, 1901. The bills were the result of

ruthless transporation competition in the city of Philadelphia between corporations

like the United and Consolidated Traction Companies, and much lobbying by powerful

interests throughout the state, including the Olivers and Mellons of Pittsburgh,

wishing to construct electrified traction lines to compete with established passenger

railroads. The following day the Pittsburgh Railways Company was founded.

The Emery Bill amended the act of May 14, 1899,

which further amended the Transit Laws passed by the Pennsylvania legislature in 1895

relating to the establishment and consolidation of street railways. The bill provides

that, whenever a charter shall hereafter be granted to build a road, no other charter

to build a road on the same streets, highways, bridges, or property shall be granted

to any other company "within the time during which, by the provision of this act, the

company first securing the charter has the right to commence and complete this work."

The right was further given the companies incorporated under the act "to take, hold,

purchase, operate, lease, and convey such real and personal property, estate, and

franchises as the purposes of the corporation shall require."

The legislation outlined the conditions under

which the new companies could use the tracks of existing corporations. It gives the

former the right to use tracks and all streets for which franchises have been granted,

but which are not "in constant daily use," and not more than 25,000 feet " of the single

or double tracks of, or the streets, highways, and bridges occupied by, any other

passenger railway company or companies, incorporated under this or any general or

special act, whether the said corporation owning the said tracks shall or shall not

have the exclusive right to lay tracks in said street or highway, either by virtue of

their charter or any legislation claiming to confer such exclusive privilege," provided

that the consent of the local authorities for such use of the tracks is first

secured.

It also requires that the consent of local

authorities shall first be obtained before any company shall have the right to

construct a road, and that the route shall be continuous. Another section requires

that the application to the local authorities must be made within two years from the

date of incorporation, and that the road must be completed within five years thereafter.

The companies are given the right "to acquire property, either by purchase or otherwise,"

but are forbidden to connect their tracks with steam-railroad tracks.

The Focht Bill is entitled "An act to provide for

the incorporation and government of passenger railways either elevated or underground,

or partly elevated and partly underground, with surface rights." After providing for

the requirements of incorporation and defining the powers and privileges of companies

incorporated under it, this bill confers the right of eminent domain upon them. The act,

which is a companion to the Emery act, has similar provisions as to the consent of local

authorities, and the time within which such application must be made and within which

the work must be completed. Moreover, the franchises were to be exclusive and perpetual,

and the companies were to have unlimited powers to borrow money on bonds.

Called "Ripper" bills, the legislation led to

rampant stock fraud by numerous entities in the region as outlined by Mayor William A.

Magee a decade later. These charges were published in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette on

December 4, 1910.

History has proven that the Focht-Emery Bills,

which were rushed through the legislature by politicians and financial magnates that

benefited greatly from the vast property and financial powers granted in the acts.

By 1906, the Pittsburgh Railways Company had grown into a consolidation of over 280 separate

corporations, either owned or

leased.

♦ The 280 Companies That Made Up Pittsburgh Railways ♦

(as of October 25, 1906)

In 1918, Pittsburgh Railways filed for bankruptcy

as interest on numerous subsidiary bond issues were in default and general mismanagement

doomed the transit giant. The Pittsburgh Railways Agreement of January 1922 between the

company and the City of Pittsburgh, which was ratified in 1924, cleared up much of the

financial and management issues, keeping the $62.5 million transit company solvent.

Another bankruptcy claim followed in 1938, and the company was eventually purchased by

the Port Authority of Allegheny County in 1964.

Despite their many flaws, the Focht-Emery Bills

did lead to the creation of a modern electrified railway system that brought public

transportation throughout the city of Pittsburgh and surrounding suburbs into the

20th century and led to unprecedented growth in the region.

Charleroi Short-Line Railway

The 39-Brookline trolley route had roots

in the Charleroi Short Line Railway. In the late-1890s, the Mellon family made

large capital expenditures in new electrified interurban traction lines. Their great

system of modern railways would feature brightly colored yellow cars that carried

a new type of braking system developed by the Westinghouse Company.

In 1901, work began on three new lines:

East Pittsburgh to Pitcairn, Wilkinsburg to Oakmont, and West Liberty to Charleroi.

The southern line would utilize the existing Pittsburgh and Birmingham Traction Company

tracks to reach Pittsburgh.

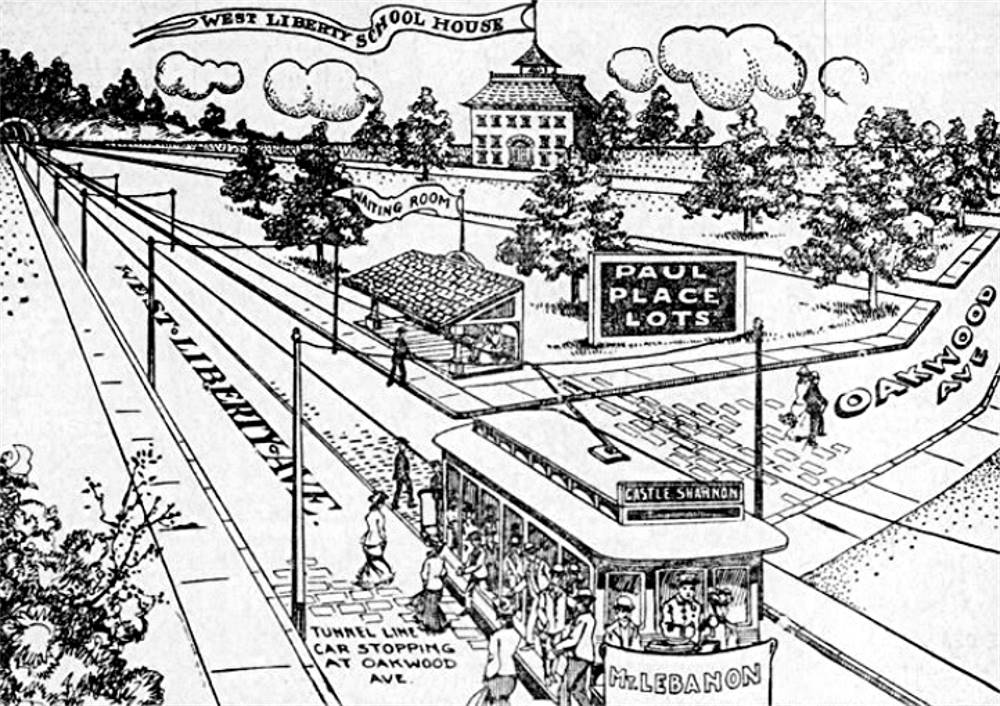

This June 18, 1904 real estate advertisement

illustration shows how vital the trolley line was to development

in Brookline. West Liberty Elementary School, atop the hill along Pioneer Avenue,

had just been enlarged.

In this image Oakwood Avenue is Capital Avenue. Paul Place was one of the original

Brookline subdivisions.

The Charleroi Short Line was a 27 1/2

mile traction line running from downtown Pittsburgh to Fayette City in Washington

County. The path chosen for this modern high-speed southern railway would be perhaps

the most significant development for the history of communities like Brookline,

Beechwood, Dormont and Mount Lebanon.

Beginning downtown at the Union Station,

single-truck cars would pass over the Smithfield Street Bridge to Carson Street, then up Brownsville Road (Arlington

Avenue) to a junction with Warrington Avenue. Once at the Knoxville Incline Station,

passengers transferred from the single-truck cars to the double-truck Mellon interurban

cars. This transfer was necessary because it was deemed unsafe to take the larger

double-truck cars along the sharp curves on Brownsville Road. From there it

was down Warrington to the South Hills Junction.

It was from the South Hills Junction that twenty-six

miles of new traction line extended to the south. The route would take the interurban

cars along West Liberty Avenue past Brookline, Beechwood and Dormont to Mount Lebanon.

The line continued on to the south, passing the P&CSRR repair yard along Castle Shannon

Boulevard on the way to Washington County.

Beginning in the spring of 1901 Pittsburgh Railways

began running traction cars along the initial single-track line to Castle Shannon and

back. It was these trolley cars that are shown in the early advertisements for homes in

Brookline's initial Fleming Place, Hughey Farms and Paul

Place housing developments.

On September 28, 1903, the Pittsburgh Daily

Post announced the formal opening of the entire traction line Pittsburgh to Charleroi.

After nearly two years and a cost of $1 million, the high-speed electrified line was

a major time saving alternative to steam locomotive travel, running exclusively on a

private right-of-way through several large boroughs.

One of the major components of the Charleroi

Short Line was the Mount Washington Transit Tunnel, which when complete would eliminate the trip over Mount Washington and

the need to switch cars, thus significantly slashing travel time even further and

fueling the first South Hills commercial and residential development

boom.

The Mount Washington Transit Tunnel opened in December 1904 and led to rapid

development in the South Hills.

West Liberty Street Railway

Company

The history of the electrified railway systems

in Pittsburgh and Allegheny really took off in the 1890s, when hundreds of traction

companies were formed, many of which were up and running when leased or acquired, then

consolidated by the Pittsburgh Railways in January 1902.

One of these was the WEST LIBERTY STREET RAILWAY

COMPANY, incorporated on October 13, 1899, to construct a line running from the intersection

of Warrington and Beltzhoover Avenues to West Liberty Avenue, then south to the Mount

Lebanon Cemetery and back. The company began with an initial stock valuation of $12,000,

which was increased in June 21, 1900, to $400,000. This was funded with a bond issue

to cover "construction of the lines and the acquisition of Rights of Ways."

On August 9, 1900 the company entered into a

consolidation agreement with the long-running Pittsburgh and Birmingham Traction Company,

a subsidiary of the state-wide United Traction Company. All were controlled by the

powerful transit conglomerate, the Philadelphia Company.

The deal consolidated their lines as part of a

continuous track system extending from Mount Lebanon to the Union Depot in downtown

Pittsburgh. This combined line would become the northern leg of the 27 1/2 mile Charleroi

Short Line Railway. Under the agreement, the West Liberty Street Railways Company became

a subsidiary of the Pittsburgh and Birmingham Traction Company.

The West Liberty Street Railway Company's tracks

were operational by the spring of 1901, spurring residential and commercial development

all along its path. The company's assets were then leased by Pittsburgh Railways Company.

The company itself remained an active corporation until 1964, when Pittsburgh Railways

was acquired by the Port Authority of Allegheny County. The West Liberty Street Railway

Company is still on the books, over 120 years after forming.

A Pittsburgh Railways Mount Lebanon

trolley car on West Liberty Avenue, just north of Brookside Avenue.

From 1901 to 1905 the new electric railway had only a single track laid

along West Liberty Avenue.

These tracks were leased to Pittsburgh Railways by the West Liberty

Street Railway Company.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

West Liberty Street and Suburban Railway

Company

Another such traction company was the WEST

LIBERTY AND SUBURBAN STREET RAILWAY COMPANY, formed on February 20, 1905. In anticipation

of the upcoming West Liberty Improvement Company development of the soon-to-be Brookline

community, investors formed this transit corporation with $6000 in capital stock to

acquire property rights for the establishment of a one-mile spur line that would branch

off of the original West Liberty Street Railway Company tracks.

The route of the proposed electrified traction

line would be as follows (reprinted verbatim from the company Articles of

Association):

Beginning on West Liberty Avenue at the

intersection with Hunter Avenue in West Liberty Borough, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania;

thence along Hunter Avenue to Lang Avenue; thence along Lang Avenue to Knowlson Avenue;

thence along Knowlson Avenue to the Hughey Road, all in West Liberty Borough; thence

continuing along Knowlson Avenue in Baldwin Township, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania,

to the township road (sometimes called Fairhaven Street) leading to Fairhaven, and

thence returning by the same route to the place of beginning, with the necessary

sidings, turnouts and switches, forming a complete circuit with its own tracks; said

road to be double track road.

Locals would know this route as:

39-BROOKLINE.

The only difference in the Brookline route as

described above and what was installed shortly afterward was that instead of running

up steep Hunter Avenue (Bodkin) to Lang Avenue (Pioneer), a looping right-of-way was

acquired that circled on a gradual grade through the Fleming Place Plan to Lang

Avenue.

The West Liberty and Suburban Street Railway

Company was acquired shortly afterwards by Pittsburgh Railways and is still on the

books, over 115 years after incorporating.

As the Pittsburgh Railways network quickly grew

to its peak in the 1920s, hundreds of these short-lived corporations were formed to

cover extensions in existing routes. Pittsburgh Railways history is a huge, interlocking

maze of mergers, leases and acquisitions.

♦ Pittsburgh Light Rail Transportation

History ♦

(including video of the Brookline Route)

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Library and West Liberty Street Railway

Company

One other traction company that established a

line significant to Brookline was the LIBRARY AND WEST LIBERTY STREET RAILWAY COMPANY,

formed on January 6, 1905. This route followed the old Pittsburgh and Castle Shannon

Railroad right of way to Castle Shannon, then continued on to Library PA. This route

was first opened to trolley traffic in July 1909 after the existing railroad line and

bridges were modified for use by electrified traction cars.

When the Shannon-Library line went into service

the larger interurban cars of the Charleroi Short Line were routed off of West Liberty

Avenue and onto this new suburban line, which intersected with the existing Charleroi

line at Willow Avenue in Castle Shannon. Like the other two local traction companies, the

Library and West Liberty Street Railway Company is still on the books as a county orphan

corporation.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Early Electrical Issues Along

West Liberty Avenue

The Pittsburgh Daily Post, on July 10, 1901,

reported that the Postal Telegraph and Cable Company went to court with the West

Liberty Street Railway Company asking for an injunction to restrain the transit company

from interferring with the poles and lines of the telegraph company in West Liberty

Borough and Scott Township.

It was said that in grading West Liberty

Avenue for the streetcar tracks the ground was dug away from the telegraph poles

in such a manner as to endanger their safety and use.

The company was also alleged that the

traction company placed their poles and wires in such a way as to interfere with

the operations of the telegraph lines. The complaint charged that the heavy current

running the trolleys burned out the appliances of the telegraph company. It was noted

that on two seperate occasions fourteen individual telegraph lines had been completely

disabled since the traction line began operation.

The communications company agreed to remove

their poles and relocate their equipment to utility poles along streets without

traction lines. The outcome of the court case is unknown, but the Postal Telegraph

and Cable Company poles were eventually moved.

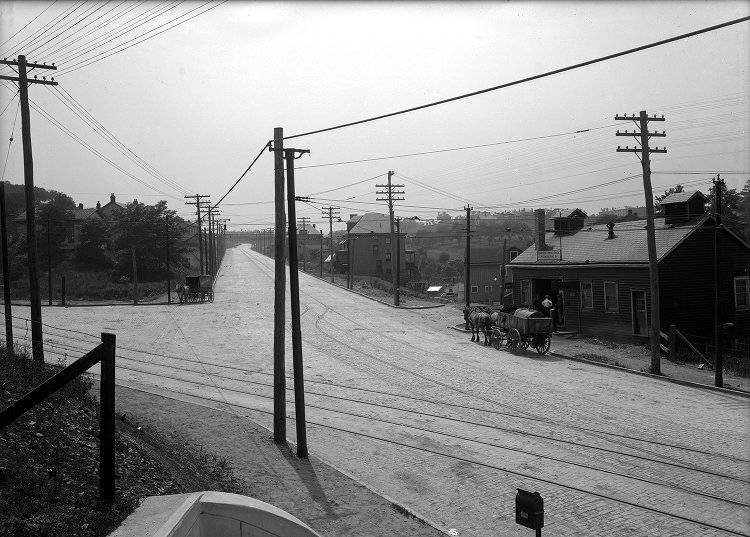

The South Hills Junction in 1906. Note the

outbound P&CSRR train on the hillside above the complex.

Freehold Real Estate Company advertisement

from June 27, 1905 highlighting Brookline's high-speed traction line.

Click on picture to see the details in a high resolution image of the

trolley scene.

In March 1905 work began on a double-track

trolley line through Brookline. To access the emerging neighborhood, an outbound

car from Pittsburgh followed the single-track Charleroi line along West Liberty

Avenue to the Brookline Junction. From there the trolley car turned left onto an

exclusive double-tracked right-of-way that wound its way along an orchard and

the Fleming Place plan of homes up a steady grade to Pioneer Avenue.

From Pioneer Avenue, the Brookline route was

double-tracked all the way along Brookline Boulevard to the city line at Edgebrook

Avenue. The two tracks continued for a short distance into Baldwin Township to

Fairhaven Road (Breining Street), where the tracks merged into a single line that

led to a loop along what is now the 1400 block of Brookline Boulevard.

An October 17, 1905 illustration depicting the

double-tracking of West Liberty Avenue.

Once at the loop the conductor had to get out

of the car and check in on a call box before beginning the 15-minute return trip to

town following the same route. Before the switches were automated, the conductor

was also responsible for manually activating a track switch at both the Brookline

Junction and Fairhaven Road. By the end of 1905, West Liberty Avenue was also

double-tracked.

Designated Route Number 39 on the Pittsburgh

Railways books, the Brookline route remained unchanged until 1966.

An inbound 39-Brookline passes Birchland Street

after the turn-around at the Brookline Loop.

Proposed Route Extension

In 1905, the Pittsburgh Railways

Company leased the Pittsburgh and Castle Shannon Railroad line with plans to convert the

steam powered line into part of the Charleroi interurban line, eliminating travel on

the increasingly congested West Liberty traffic corridor.

Early community planners envisioned two distinct

Brookline streetcar routes. One was the traditional route that ran to the loop along

the 1400 block of the boulevard and then headed back in the opposite direction. The

additional route would switch off to the right near present-day Birchland Street and

continue along a one-way single track line through the Fairhaven Valley to Saw Mill

Run along following the path of an old Pittsburgh and Castle Shannon

Railroad spur line that ran

along the valley floor.

From there the tracks would merge with the

main Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon Railroad line, the tracks of which were scheduled to

be modified for use by electified traction cars and in service by 1909. Once this

Brookline/Fairhaven extension merged onto the Castle Shannon line the trolley the

inbound route followed the Saw Mill Run corridor to the South Hills Junction. The proposed route would be a continuous wider ranging single-direction

loop from downtown to Brookline intended to serve the planned East Brookline and

Brookdale developments.

In anticipation of this alternate

Brookline/Fairhaven route, the Pittsburgh Railways Company acquired the right-of-way

through the valley. This extended route is prominently displayed on old real estate

advertisements appearing in the first few years of the community's development. The

Fairhaven extension is also shown on Hopkins Plot Maps as late as 1940.

The Overbrook Tunnel was constructed in

1909 by the West Side Belt Railway. Shown here in 2013,

the tunnel was originally built as a pass-through for the 39-Brookline.

When the West Side Belt Railway upgraded it's

Pittsburgh lines in 1909, the Overbrook trestle that carried trains over the Fairhaven

valley was replaced with the present-day Overbrook Tunnel and a solid earth abutment.

Anticipating that the trolley route would one day pass through the tunnel engineers

placed metal hooks on the tunnel walls for the trolley's electric guide lines. Some

of these pins are still visible today.

In April 1909, Pittsburgh Railways began

electrifying and converting the P&CSRR rail gauge to accommodate the light rail

traffic. Standard streetcars and the larger interurban cars began running along

that line in July of that year. The entire project, including the retrofitting of

four bridges, was completed in December 1910 at a total cost of $161,000.

It is unknown exactly why planners decided

to abandon the route through the Fairhaven Valley to Saw Mill Run, but despite

repeated efforts over the years to improve that land (known to planners as the

Brookdale development), the concept never materialized and the Brookline Loop near

Witt remained the furthest extent of the 39-Brookline route for the next half

century.

The frequent and reliable streetcar service

became, for many years, the primary mode of transportation to and from downtown

Pittsburgh, or maybe just from one end of the community to the other. Hundreds of

miles of rail lines now linked all of Pittsburgh's communities, and interurban routes

stretched far beyond the reach of the metropolitan area.

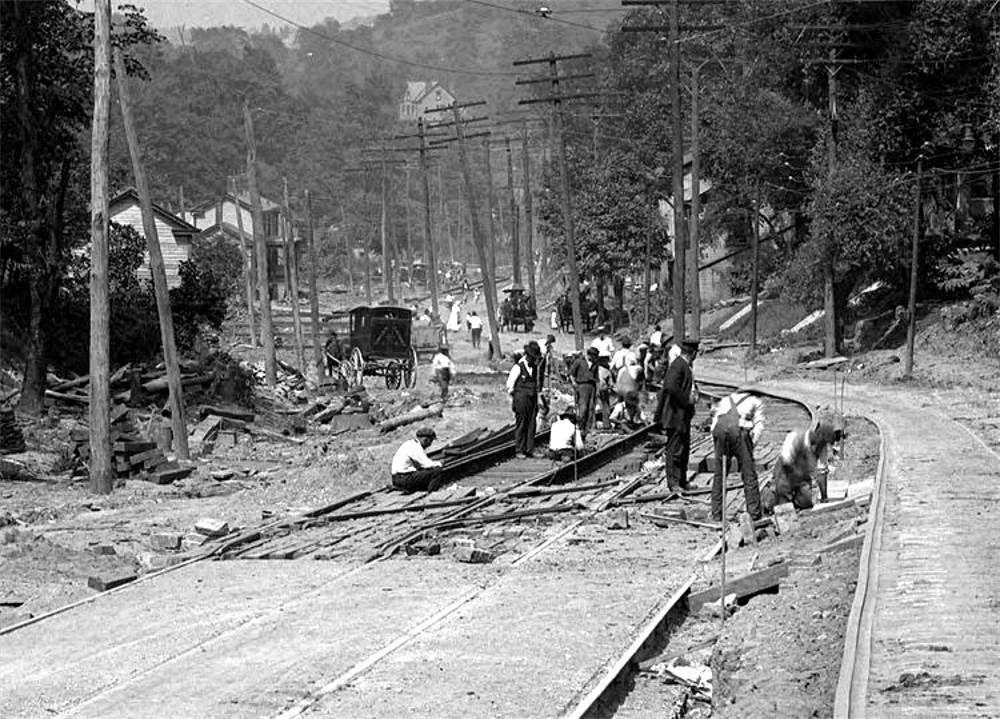

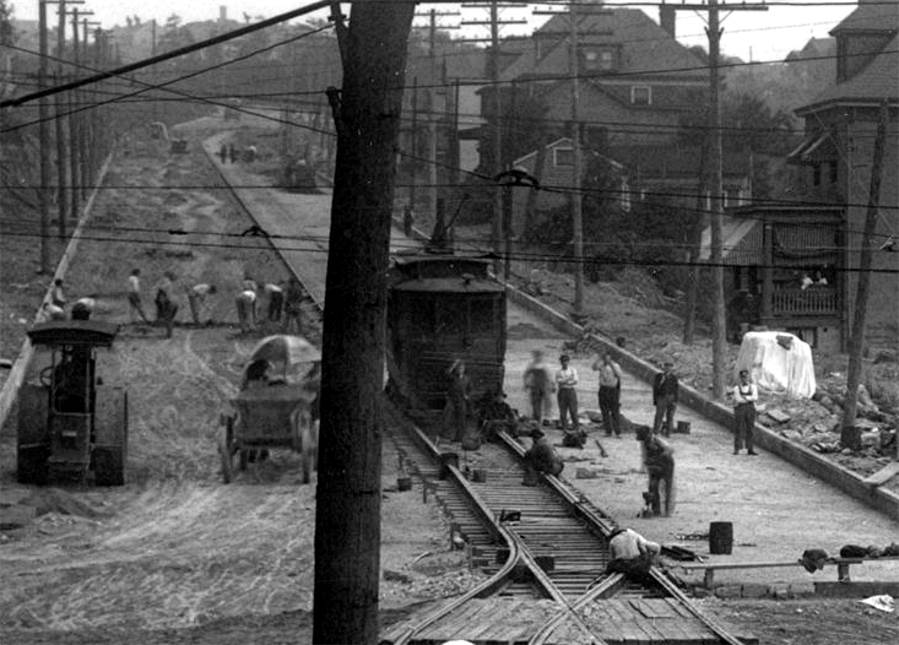

Workers installing new double-track rails

during the West Liberty Avenue reconstruction project in August 1915.

The view is looking north from near Belle Isle Avenue towards Pauline and

on to the bend leading to Capital.

A major upgrade to the Brookline route

occurred in 1915, when the entire length of the traction line was reconstructed along West Liberty Avenue. Twenty years later, in 1935, another significant

improvement was the reconstruction of Brookline Boulevard, when the exclusive trolley right-of-way from West

Liberty to Brookline Boulevard and Pioneer Avenue was expanded and paved with belgian

block. Brookline Boulevard was permanently re-routed onto the widened, looping roadway,

which would be used for both vehicular and rail traffic.

Then, in 1939, streetcars were diverted

away from the congested West Liberty Avenue/Saw Mill Run Boulevard intersection

with the construction of a trolley ramp built slightly north of Pioneer Avenue. The trolley line then merged

with the Beechview line and crossed the Palm Garden Trestle to enter the South

Hills Junction complex.

August 9, 1939 - work proceeds on

the West Liberty Avenue Trolley Ramp. In one week it would open to traffic.

Trolleys Used In Brookline

The first generation of electrified

trolley cars used here in Brookline were old wooden cars covered in steel-sheeting,

referred to as "box cars." They were built by the St. Louis Car Company at a cost

of $6000 each and introduced in Pittsburgh during the winter of 1902.

These eight-wheelers were forty-seven feet

long and powered by four fifty-horse power motors. The cars had high floors,

narrow doors and sat forty-four passengers on wooden seats. They could be driven

from either side of the vehicle by moving directional controls and electrical guide

wire from one end to the other. Although reliable, these early streetcars were deemed

uncomfortable by passengers and phased out in the early-1920s.

Two inbound 39-Brookline streetcars

on West Liberty Avenue, approaching Capital Avenue, in September 1915.

These were the original eight-wheeled "box cars" that made up the bulk

of the Pittsburgh fleet at the time.

From 1915 to 1927, Pittsburgh Railways

contracted with the Pressed Steel Company, located in McKees Rocks, for 1000

of the their new steel-framed "Jones Cars." The forty-foot, double-ended,

sixteen-wheel streetcars featured cushioned rattan seats, a lower-floor, fine

woodwork and windows that opened to let in fresh air. They were quite an upgrade

in passenger safety and comfort, and the additional seating capacity helped ease

overcrowding.

The original Jones Car color scheme was

maroon with gold trim. In 1925 the Pittsburgh fleet was painted chrome orange to

increase visibility in the "Smokey City." The elements, combined with the

ever-present pollution from surrounding industry soon faded that color to a dull,

yellowish tint. Here in Pittsburgh, this generation of trolley cars became

commonly known as "Yellow Cars." This model remained in service until phased out

in 1954. Modified Jones Cars remained in the fleet as maintenance and support

vehicles into the 1960s.

A Jones Car marked for the 39-Brookline route

stands at the South Hills Junction in 1948.

In 1936, at the request of the American

Electric Railway Association Advisory Council, the St. Louis Car Company, with

help from Pittsburgh's Westinghouse Company, introduced the sleek new vehicles.

Since the project development was overseen by the Electric Railway Presidents

Conference Committee, the design was branded with that name.

Considered revolutionary in their time,

these ultra-modern red and cream colored vehicles would soon become the standard

cars in the Pittsburgh Railways fleet. The first Presidents Conference Committee

(PCC) car arrived in Pittsburgh that year. Car #100 entered service on September

26, 1936, and was used on all routes to promote ridership around the

city.

Pittsburgh Railways ordered 666 of the

Presidents Conference Committee cars, at a price of $28,000 apiece. They entered

the fleet in 1937 and served the city and surrounding suburbs for a half

century.

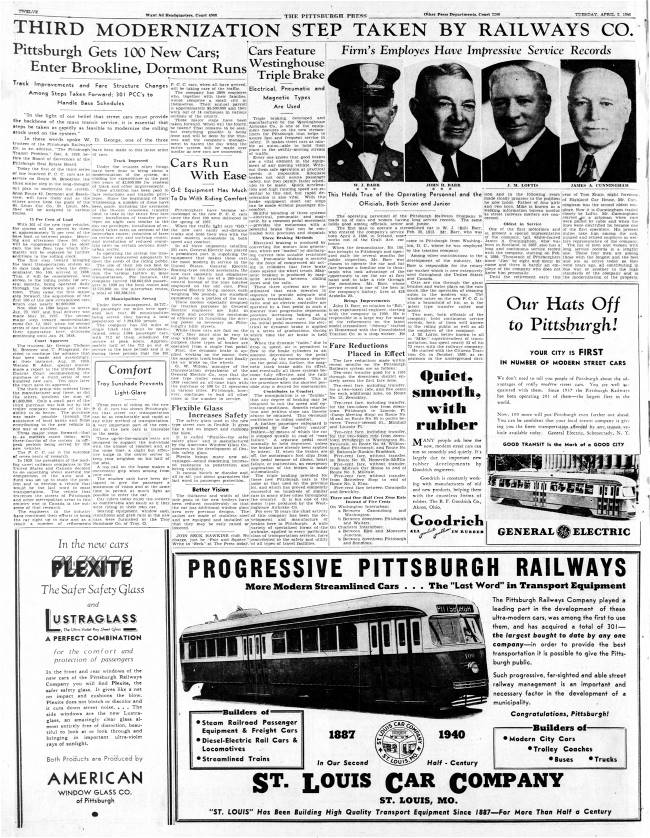

On April 2, 1940, the company

took delivery of the third shipment of 100 cars, bringing the fleet total to

301. The PCC cars began running regularly on the Brookline route. By the 1990s,

only a handful of PCC cars were left in operation, running only along the

southernmost section of the Shannon-Library route. The remaining three

PCC cars were retired in September 1999.

President's Conference Committee models

carried Brookline commuters for twenty-seven years.

Presidents Conference Committee

Cars

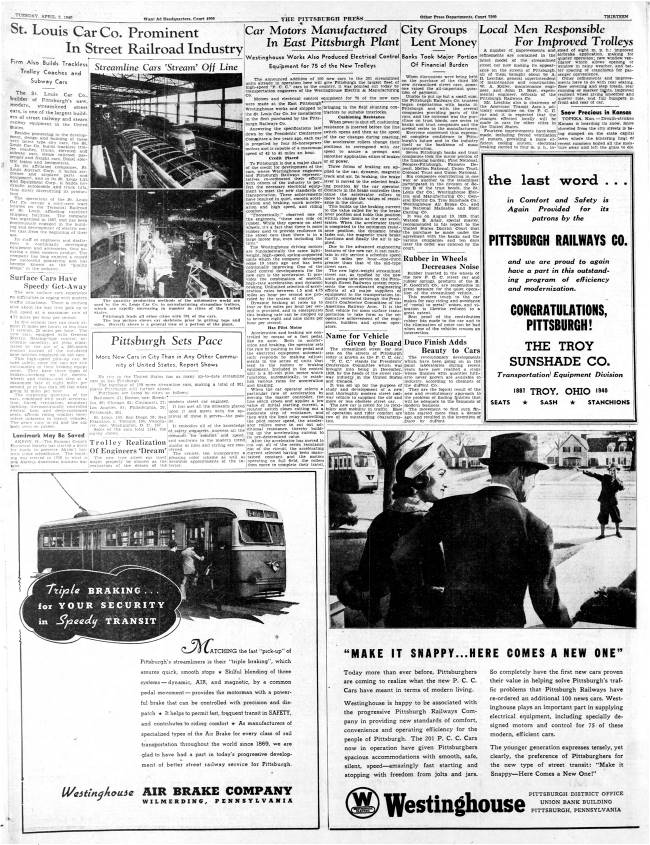

Below is a five-page feature that ran

in the Pittsburgh Press on February 2, 1937. This was the day that the first

shipment of 100 Presidents Conference Committee (PCC) cars went into service

for the Pittsburgh Railways Company.

The associated articles detail the many

technological improvements made in the new traction cars and the contributions

of Pittsburgh industry towards their development.

* Click on newspaper

images for larger readable version *

Inbound 39-Brookline rolling along Smithfield

Street, after passing the Boulevard of the Allies, on June 27, 1965.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

The following two page feature was

published in the Pittsburgh Press on April 2, 1940. This was the day that

the third installment of 100 PCC trolley cars went into service with the

Pittsburgh Railways network.

One of the articles announces the beginning

of PCC car service along the 39-Brookline route and the others detail the

many improvements made in the motor and braking systems of this latest

model. These were designed and manufactured here in Pittsburgh by the

Westinghouse Company.

* Click on newspaper

images for larger readable version *

Riding The Streetcar To

South Hills High School

The Pittsburgh Public School

Board opened South Hills High School, in 1917. Located along Ruth Street in Mount

Washington, the high school served students from Mount Washington,

Banksville, Beechview and Brookline for sixty years, until

1977.

Conveniently located on the hill

above the Pittsburgh Railways' South Hills Junction, a set of city steps

led to Paul Street, and from there it was a short walk to the school

along Ruth Street.

Public transportation was the best

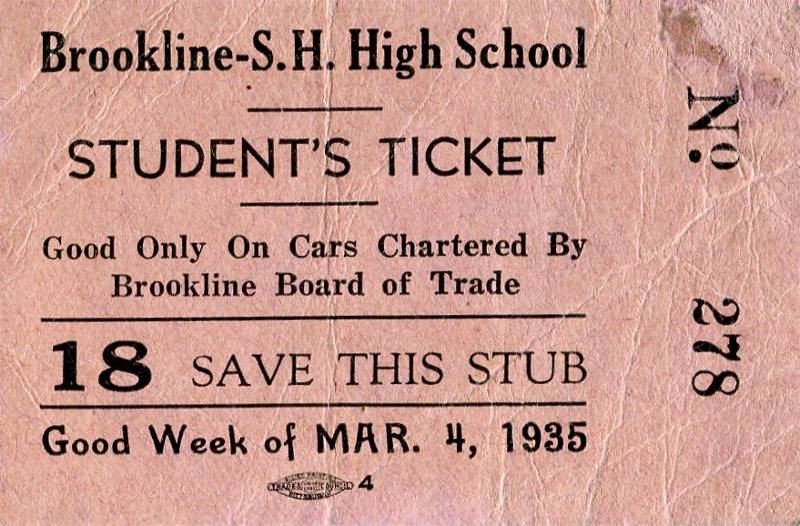

alternative to transport students from Brookline and Beechview to and from

school, but the company was unwilling to give school discounts. Students

who rode the streetcar always paid a full fair.

A Pittsburgh Press clipping from October 29,

1934, touting new transportation arrangement for Brookline students.

An interesting solution was found.

The Brookline Board of Trade and the Beechview Democratic Workers each

began renting streetcars at $5/hour. Students were sold tickets each month

at a rate of five cents each.

So many students became riders that

Brookline was renting four buses. But, in the end, the plan worked so well

that it actually lowered the per-student fare to only four cents per trip,

less than the predicted five cents and a far cry from the standard ten cent

fare.

A Pittsburgh Sun Telegraph clipping from

March 21, 1935.

Streetcars line up at the South Hills

Junction in 1935 to transport South Hills High School students home to

Brookline and Beechview (left); A gathering of students boarding a streetcar

at the Junction in 1963.

In later years, the Board of Trade

and the Pittsburgh School Board came to aggreement and the streetcars became

basic school-day transport. Starting in 1966, Brookline students began taking

buses rather than the streetcars, still subsidized by the Chamber of Commerce,

as the local rail route was discontinued.

For the generations of Brookline

teenagers who attended South Hills High School, their school days were filled

with many memories. One remembrance that most look back on with fondness was their

daily ride on the 39-Brookline, especially the trip home from school.

A Brookline trolley stands second in line

ready to pick up students from South Hills High School circa 1961.

Brookline Streetcar Route

Discontinued

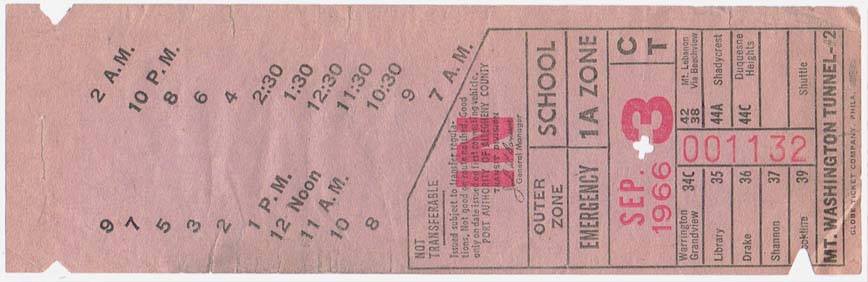

The last run of the 39-Brookline

streetcar took place on September 3, 1966. Trolley enthusiasts gathered

for one final trip on a chartered PCC car that made a ceremonial run

along the sixty-one year old Brookline route. When the trip was completed,

John Damerson, Director of the Port Authority, signed the final transfer

slip to mark the occasion.

The following day, Port Authority

bus service replaced

the old trolley service and the local route was given a new designation,

41-Brookline. Within a few months, the old tracks that ran down the center

of Brookline Boulevard were paved over. The divided section of the road

from Edgebrook Avenue to Breining Street was widened to a broad,

four-lane avenue.

Red and cream colored PCC trolley cars travel

along Brookline Boulevard in 1966.

The era of rail traffic through

the heart of the Brookline community had come to an end. Many Brookliners

lamented the loss of the vintage streetcar service. However, as time went

on, they embraced the new Port Authority bus service as a reliable and

convenient public transportation alternative.

Reminders Of Yesteryear

The trolleys may have disappeared

from the Brookline landscape, but the old rails remained buried under the

asphalt. They occasionally made themselves a visible reminder of the

the community's streetcar past when a deep pothole emerged.

An inbound 39-Brookline approaching Flatbush

Avenue on Brookline Boulevard in the Summer of 1966.

The old tracks were briefly exposed,

in their entirity, during the reconstruction of Brookline Boulevard in 2014. When the aging asphalt was milled

down to the base, the four lines of steel tracks once again stretched down

the center of the boulevard.

For a brief time, Brookliners could

once again gaze at these historic remnants of the community's railway heritage.

After just two days above ground, the tracks were again hidden under eight

inches of black top.

An outbound 39-Brookline passes Kenilworth Avenue

in August 1966.

Another throwback to yesteryear came

in 2011. During a reorganization of the Port Authority bus service here in

Pittsburgh, Brookline's route designation was changed back to number thirty-nine,

a number not scene in the neighborhood since 1966. When a bus now makes the local

run, the marquee is emblazened with the vintage 39-Brookline.

One final reminder of the era of Pittsburgh

Railways and the trolleys that played a part in the birth of Brookline are located

here and there, mostly in collector albums or attic drawers. These are the various

fare tokens issued by Pittsburgh Railways over the years. The most common are the

1922 variety, a 3/4 inch brass token emblazened with an image of a Jones Car and

distinguishable by the triangle cut in the center.

A 39-Brookline streetcar at the trolley loop

along the 1400 block of Brookline Boulevard.

A Slice Of Americana

Brookline's trolleys may be gone,

but they will never be forgotten. The four-wheel box cars, the yellowish

Jones Cars, the red and cream PCC Cars, and the steel rails will forever

be a part of Brookline's transportation heritage that evoke nostalgic

memories.

An outbound Brookline trolley at the Queensboro

Avenue crosswalk in 1965.

Urban rail car enthusiasts still yearn

for the thrill of riding the rails through the city landscape. Photos of the

39-Brookline trolleys, making their way past the Boulevard shops, are like a

classic Norman Rockwell slice of Americana.

39-Brookline trolleys at the turn-around

loop at the end of the Brookline route.

A final historical note on the PCC cars of the

old Pittsburgh fleet. A few are scattered about in Trolley Museums around the country.

Others were sent to the San Francisco Bay area, where they provided much-needed

replacement parts for vintage PCC cars that remain in operation, ferrying

passengers through the Old Town to the harbor.

Take A Ride On The "T"

For those who still have an itch

to ride the rails, the Port Authority's "T", a modern light rail

system, still operates

along the old Shannon-Drake, Shannon-Library, Beechview and Mount Lebanon routes.

The Potomac Station in Dormont is just a short drive or a brisk walk for

most Brookliners, making the "T" a viable alternative for local commuters.

Light rail cars pass the Station

Square stop at Carson and Smithfield Streets.

The Port Authority's subway system

connects these southern light rail routes with locations throughout downtown

Pittsburgh and the North Shore. A quiet ride to South Hills Village or a run

to the Library suburbs is reminiscent of the old days.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Light-Rail Service Comes To

Brookline

Although Brookline lost it's direct

streetcar route in September 1966, residents of East Brookline could still

walk down the Jacob Street Steps and through the Overbrook Tunnel to a car

stop along the Shannon-Drake line. This was the only streetcar stop located

within the confines of the Brookline community.

The Port Authority's Shannon-Drake

line ran along the route of the old Pittsburgh and Castle Shannon Railroad.

In the Saw Mill Run valley it passed through Bon Air and Carrick on the

northern side, then crossed over to the southern side of Saw Mill Run at

Whited Street.

The line then passed through a small

section of Brookline, where the local Car Stop stood near Overbrook Elementary

School. This long-serving streetcar line, one of the oldest in the South

Hills, was discontinued in 1993.

South Bank Station is a light-rail

transit stop located within the Brookline community.

After the turn of the century, the

Port Authority began a reconstruction project along the length of the

Shannon-Drake route to convert it to the modern light-rail system. Due to

elevation changes in the new line, the Overbrook station was

eliminated.

When the refurbished rail line

opened in 2004, a passenger platform was installed near Jacob Street.

between Whited Street and the lower end of Brookline Boulevard. It is

located the portion of the route that is shared by the rail line and the

South Busway.

Known as South Bank Station, the

bus stop had been in existence since 1977, when the South Busway opened.

Now doubling as a bus and light-rail station, South Bank has become a popular

car stop for residents living in the East Brookline part of the

neighborhood.

Brookline Streetcar Photo Gallery

(Downtown Pittsburgh to the Brookline Loop)

♦ Downtown Pittsburgh ♦

♦ South Hills Junction ♦

♦ West Liberty Avenue to the Brookline Junction ♦

♦ Brookline Boulevard from West Liberty to Pioneer ♦

♦ Brookline Boulevard Commercial District ♦

♦ Brookline Boulevard from Edgebrook to Breining ♦

♦ Breining Street to the Brookline Loop ♦

♦ Pittsburgh Light Rail Transportation

History ♦

(including video of the Brookline Route)

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Downtown Pittsburgh

Inbound 39-Brookline crosses East Carson

Street onto the Smithfield Street Bridge.

An inbound 39-Brookline on the Smithfield Street

Bridge (left) and another heading outbound at Carson Street.

Outbound 39-Brookline on the Smithfield

Street Bridge heading towards Carson Street and the transit tunnel.

39-Brookline passes the First English Evangelical

Lutheran Church along Grant Street - June 27, 1965.

39-Brookline at Mellon Plaza on Smithfield

Street (left) and another passing the City County Building on Grant Street.

Outbound 39-Brookline makes the turn off

the First Street ramp onto the Smithfield Street Bridge.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

South Hills Junction

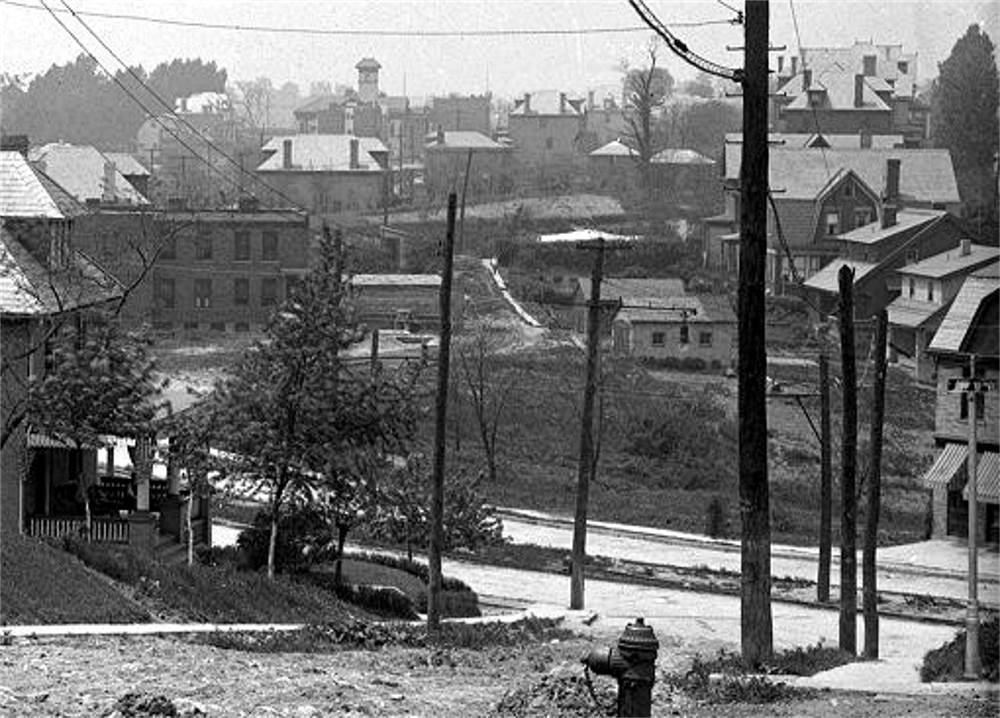

Looking down upon the Pittsburgh Railways

South Hills Junction in the spring of 1905 from the P&CSRR tracks

above.

Looking from atop South Hills High School

along Ruth Street down at the southern approaches to the South Hills

Junction in 1918. The Shannon and Charleroi lines come in from the left and the

Brookline, Beechview, Dormont

and Mt. Lebanon lines to the right. Homes along Warrington Avenue can be seen to

the left.

A 39-Brookline PCC passes an old Jones Car as

it approaches the South Hills Junction.

An outbound 39-Brookline at the Junction Car

Stop (left) and an inbound approaches the transit tunnel entrance.

An inbound 39-Brookline passes through

the South Hills Junction.

39-Brookline trolleys crossing the Palm

Garden trestle on their way toward the South Hills Junction.

A 39-Brookline trolley passing through

the South Hills Junction yard in 1959.

An outbound 39-Brookline exits the transit

tunnel (left) and another passes the car barn at the Junction.

A 39-Brookline PCC passes through the

South Hills Junction.

1960s-era overhead view of the South Hills Junction

rail yard complex.

A 39-Brookline PCC stands in line waiting to take

to the tracks South Hills Junction.

Inbound 39-Brookline trolleys pass the outbound

Junction loading platform on the way to the transit tunnel.

A 39-Brookline PCC passes through the

South Hills Junction.

A 42/38-Mt Lebanon/Beechview on the

Parm Garden Trestle (left). The 39-Brookline streetcar used the bridge

from 1940 to 1966. To the right, a 39-Brookline enters the

trolley ramp heading towards West Liberty.

An inbound 39-Brookline merges onto the Beechview

line at the top of the West Liberty Avenue ramp.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

West Liberty Avenue

A trolley car passes homes along West Liberty

Avenue, north of Brookside Avenue (circa 1904).

By the end of 1905 the streetcar line along West Liberty Avenue would be

double-tracked.

An outbound streetcar approaches Brookside

Avenue and a billboard advertising lots in Brookline (left),

and an inbound streetcar passing Stetson Street heading north towards

Cape May in March 1915.

An outbound streetcar approaches Belle Isle

Avenue in March 1915 (left) and another at Belle Isle in August 1915.

An inbound 39-Brookline streetcar heads

north towards Cape May Avenue in March 1912.

Two inbound 39-Brookline streetcars approach

the Capital Avenue on West Liberty Avenue (left), and a

well-dressed family wait for a streetcar at the Capital Avenue

Car Stop in September 1915.

Construction work at the Brookline Junction in

May (left) and in August 1915, looking south towards the city line.

A man and three boys pass Stetson Street as

they ride the rails south towards Capital in August 1915. The young

lad standing on the edge of the wagon is looking back at a streetcar coming

up behind the wagon.

An inbound streetcar passes Pioneer Avenue

approaching the intersection with Warrington (left)

and another heading outbound past Cape May Avenue in December 1915.

West Liberty Avenue in 1916, looking north from

the Brookline Junction (left) and the intersection of Ray Avenue.

The year-long reconstruction project is finished. The roadway was widened

to four lanes and paved in Belgian

block. New sewers and electric has been installed as well as a complete upgrade of

the streetcar line.

An outbound streetcar passes the Brookline

Junction heading uphill towards the city line in June 1916.

A trolley car heading inbound approaches

the Pioneer Avenue Car Stop (left) in 1918; An inbound

trolley on Warrington Avenue after turning off West Liberty Avenue in

1921.

The intersection of West Liberty Avenue and

Warrington Avenue in 1918.

Prior to 1940 and the construction of the

trolley ramp, the Brookline route ran the length of West Liberty Avenue

to Saw Mill Run Boulevard. From there it turned onto Warrington

Avenue, then entered the South Hills Junction.

The trolley ramp was built to ease traffic congestion at the Liberty Tunnels

intersection. The ramp led to

a junction with the Beechview line and proceeded over the Palm Garden trestle

to The Junction.

The two photos above show the busy intersection in 1930 (left) and again in

1936.

A 1940s-era long view showing the lower end

of West Liberty Avenue,

including the trolley ramp and the Liberty Tunnels.

A 39-Brookline PCC comes off the newly

constructed West Liberty Avenue streetcar ramp in 1940 (left) and in

1965.

An outbound 39-Brookline comes down the West Liberty

Avenue trolley ramp.

A 39-Brookline heading outbound along the West

Liberty Avenue trolley ramp (left) and another

making the inbound trip, entering the ramp in 1966.

A 39-Brookline enters the West Liberty trolley

ramp (left) and an outbound car passes Cape May Avenue.

A 39-Brookline passes Downtown Pontiac's Used Car

lot heading outbound towards the Ray Avenue Stop.

Inbound streetcars at the Capital Avenue Car

Stop, on January 22, 1959 (left) and February 4, 1960.

An inbound 39-Brookline pulls onto West Liberty

Avenue from Brookline Boulevard on May 22, 1962.

Inbound 39-Brookline streetcars approaching

the Pauline Avenue (left) and Capital Avenue car stops.

An outbound 39-Brookline passes Brookside

Avenue (left) and another outbound approaches Capital Avenue.

An inbound 39-Brookline passes billboards at the

Brookline Junction as it merges onto West Liberty Avenue.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Brookline Boulevard

(West Liberty Avenue to Pioneer Avenue)

A 1909 view taken from Brookline Boulevard (Bodkin

Street) and Pioneer Avenue showing the Pittsburgh Railways

streetcar right-of-way that would one day become part of

the Boulevard Loop. At that time the Brookline

route was only a single-track line. The homes in the

distance are on Espy Avenue in Dormont.

The Brookline Junction (left) at West Liberty

Avenue in 1909, and the 39-Brookline tracks passing the front

of Harley's Express Moving and General Hauling, located at the

Brookline Junction, in 1915.

West Liberty Avenue at the intersection

with Brookline Boulevard, called the Brookline Junction, in March 1915.

The narrow dirt roadway was paved only along the trolley line, which

doubled as a pedestrian walkway.

A vintage Jones Car passing Brookline's

Fleming Car Stop in 1928.

The old trolley right-of-way at Shawhan Avenue

in July 1935, before the reconstruction of Brookline Boulevard.

Two 1935 views showing the construction

of the Boulevard Loop from Pioneer Avenue to West Liberty Avenue.

The boulevard was rerouted off of present-day Bodkin Street onto the

streetcar right-of-way.

To the left is a view of the Fleming Car Stop and to the right

a view towards Pioneer.

A web of overhead wires and the Car Stop

sign that hung at the Fleming Place stop.

West Liberty Avenue, at the intersection

with Brookline Boulevard and Wenzel Avenue, in June 1916 (left) and

an inbound trolley, a Jones Car, on Brookline Boulevard at the

Fleming Car Stop, near Kenilworth, in 1935.

An outbound 39-Brookline makes the turn

from West Liberty Avenue onto Brookline Boulevard.

A new PCC car passes the Fleming

Car Stop (left) as it heads inbound towards West Liberty Avenue in 1940,

and an outbound trolley passes Kenilworth Avenue, heading towards Pioneer

Avenue in the late-1950s.

Outbound 39-Brookline trolley cars passing Kenilworth

Street on the way up hill towards Pioneer Avenue.

An outbound 39-Brookline passes Jillson Street heading

towards West Liberty Avenue on on May 19, 1963.

Inbound 39-Brookline streetcars pass Pioneer

Avenue (left) and Kenilworth Avenue (right) enroute to West Liberty.

Outbound 39-Brookline streetcars head up Brookline

Boulevard after turning off of West Liberty Avenue in 1966.

A chartered outbound trolley passes Kenilworth

Avenue enroute to Brookline Boulevard in 1966.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Brookline Boulevard - The Commercial District

(Pioneer Avenue to Edgebrook Avenue)

Brookline Boulevard in 1910, at the

corner of Chelton Avenue. The Freehold Real Estate office is located on

the corner island where present-day Triangle Park and the Veteran's Memorial

stand. A vintage

39-Brookline four-wheel box car can be seen to the left

passing Queensboro Avenue.

A 1916 view of Brookline Boulevard, looking

towards Stebbins Avenue (left) and Brookline Boulevard, in 1926,

looking along the streetcar rails in the direction of Creedmoor

Avenue.

Looking down Creedmoor Avenue, from Clippert

to Brookline Boulevard and the streetcar tracks in 1919.

A view of the rails along Brookline Boulevard,

taken from Pioneer Avenue (left) and a 39-Brookline Jones Car

approaches the Stebbins Avenue Car Stop along Brookline Boulevard in

1933.

Inbound and outbound trolley rails cut a

path along Brookline Boulevard, near Castlegate Avenue, in 1926.

Two views of Brookline Boulevard in 1933,

near Glenarm Avenue (left) and Flatbush Avenue.

The Brookline Boulevard Commercial

District (left), looking west from Chelton Avenue and Veteran's Memorial Park.

Two streetcars are passing near Stebbins Avenue. To the right

is the passenger island at Pioneer Avenue in 1936.

Two trolley cars, one inbound and one outbound,

pass near Flatbush Avenue along Brookline Boulevard in 1965.

An inbound 39-Brookline trolley approaches

the intersection with Flatbush Avenue (left) and an

outbound car passes the intersection of Glenarm Avenue in 1965.

An outbound 39-Brookline passing the Texaco station

at the corner of Pioneer Avenue and Brookline Boulevard on June 28, 1965.

Outbound and inbound streetcars approaching

Castlegate Avenue (left) and two inbound cars near Stebbins Avenue.

An inbound trolley moves with traffic along

Brookline Boulevard on June 26, 1965.

An inbound 39-Brookline trolley passes

the intersection with Flatbush Avenue (left) and an

outbound car at the intersection of Pioneer Avenue in 1965.

An inbound trolley approaching a passenger

waiting on the island at Pioneer Avenue in 1965.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Brookline Boulevard

(Edgebrook Avenue To Breining Street)

An inbound 39-Brookline approaches a passenger

waiting to board at Whited Street on May 19, 1963.

An outbound 39-Brookline passes Edgebrook

Avenue heading downhill towards the Whited Street Car Stop.

Outbound cars approach Whited Street (left)

and Breining Street.

An outbound 39-Brookline passes Whited Street

heading downhill towards the Breining Street Car Stop.

An outbound 39-Brookline approaches Breining Street

while an inbound heads uphill towards Whited Street in 1966.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Brookline Boulevard

(Breining Street To The Trolley Loop)

A 39-Brookline streetcar at the trolley loop

preparing for the return trip up Brookline Boulevard.

Two trolleys at the Brookline Loop (left)

and another beginning the inbound trip back along Brookline Boulevard.

Two outbound 39-Brookline trolleys approaching

Breining Street on September 4, 1953 (left) and September 1, 1966.

A 39-Brookline waits for automobile traffic

to pass at the intersection of Breining Street in January 1958.

Conductor checking in at the Brookline Loop (left) and

an outbound car approaching the loop.

An outbound streetcar passes the intersection

with Birchland Street (left) and another approaches the trolley loop.

A 39-Brookline waits at the Brookline Loop

to begin its inbound run.

A 39-Brookline waits at the Brookline Loop

to begin its inbound run.

Trolley cars at the Brookline Loop along the

1400 block of Brookline Boulevard. This was the end of the local route.

Two images showing the 39-Brookline trolley cars

at the Brookline Loop in 1965.

A 39-Brookline makes the turn at the Brookline Loop

in January 1965.

Two images showing the 39-Brookline trolley cars

at the Brookline Loop in 1966.

The Brookline Loop was built in 1910 when the

local route was double-tracked. Prior to that, the Brookline route

ran into the Overbrook Valley to Saw Mill Run, where it intersected

with the Shannon and Charleroi lines.

A 39-Brookline at the Brookline Trolley Loop.

Related Links

♦ The Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon Railroad (1871-1912) ♦

♦ The Pittsburgh Railways South Hills Junction - 1904 ♦

♦ South Hills Junction to Brookline Boulevard - 1912 ♦

♦ The Mount Washington Streetcar Tunnel - 1904 ♦

♦ Reconstruction of West Liberty Avenue in 1915 ♦

♦ Reconstruction of Brookline Boulevard in 1935 ♦

♦ Reconstruction of Brookline Boulevard in 2013 ♦

♦ Brookline Junction Trolley Accident - 1930 ♦

♦ West Liberty Avenue Trolley Ramp - 1939 ♦

♦ A Short History of Trolleys in Pittsburgh ♦

♦ A Tragic Bus/Trolley Collision - 1978 ♦

♦ Pittsburgh Railways Company Records ♦

♦ Photos of Trolleys Around Pittsburgh ♦

♦ Pittsburgh Light Rail Photo Gallery ♦

♦ The "T" Light Rail Transit System ♦

♦ The Skybus Project in the 1960s ♦

♦ Pittsburgh Motor Coach Company ♦

♦ PAT Bus Service in Brookline ♦

♦ Trolley Parks in Pittsburgh ♦

♦ Pittsburgh's Old Inclines ♦

♦ Pennsylvania Trolley Museum ♦

♦ Wikipedia: Pittsburgh Light Rail ♦

♦ Wikipedia: Pittsburgh Railways Company ♦

♦ Wikipedia: Port Authority of Allegheny County ♦

♦ Pittsburgh Light Rail Transportation

History ♦

(including video of the Brookline Route)

American Motor Coach Association

of Pittsburgh

Transit History Links

♦ The Formation of PAT (1956-1964) ♦

♦ The Early Years At PAT (1964-1972) ♦

♦ Pittsburgh Area Transit History Index ♦

Transit Companies

That Made Up Pittsburgh Railways

♦ Pittsburgh Railways Company Books ♦

♦ History of the Southern Traction and Underlying Companies ♦

♦ History of the Suburban Rapid Transit and Underlying Companies ♦

♦ County Railway Companies Incorporated Under Focht-Emery Bills - Vol I ♦

♦ County Railway Companies Incorporated Under Focht-Emery Bills - Vol II ♦

♦ County Railway Companies Incorporated Under Focht-Emery Bills - Vol III ♦

♦ Allegheny County Street Railways Extending Service (6/8/01-10/1/03) ♦

♦ History of the Consolidated Traction and Underlying Companies - Vol I ♦

♦ History of the Consolidated Traction and Underlying Companies - Vol II ♦

♦ History of the United Traction and Underlying Companies - Vol I ♦

♦ History of the United Traction and Underlying Companies - Vol II ♦

♦ History Street Railway Companies (6/8/01-2/25/02) ♦

♦ History of Pittsburg Railways and Underlying Companies ♦

♦ List of the 280 Companies That Made Up Pittsburgh Railways ♦

(as of October 25, 1906)

Are They Called

Streetcars Or Trolleys?

There is some debate over whether the

proper term for the vehicles that ran the rails on Pittsburgh streets were

called "Streetcars" or "Trolleys."

The answer is ... both!

The official

terminology might sound a bit strange:

A TRAM (also known as a tramcar; a

streetcar or street car; and a trolley, trolleycar, or trolley car) is a rail

vehicle which runs on tracks along public urban streets (called street running),

and also sometimes on separate rights of way. Trams powered by electricity,

which were the most common type historically, were once called electric street

railways. Trams also included horsecar railways which were widely used in urban

areas before electrification.

For a more detailed history

of trams, visit Wikipedia (Trams).

One of the old-time Car Stop signs that hung

along overhead wires around Pittsburgh.

Just to throw a further element into the

"streetcar" or "trolley" debate, many of the old turn-of-the-century advertisements

for Brookline speak of the Transit Line and the fine "transit cars" that helped link

the neighborhood to the city of Pittsburgh. So, when in doubt, the best and most

correct answer is "Tram." However, depending upon the present company one could

choose "transit car," "trolley" or "streetcar" and fit right in with the

crowd.

An inbound 39-Brookline streetcar approaches

Carson Street in 1963.

Original Brookline Souvenirs

In 1907, during the initial residential

building boom in Brookline, the Freehold Real Estate Company offered solid sterling

silver commemorative spoons to homebuyers. With respect to the Pittsburgh

Railways streetcar line that brought this new prosperity to the emerging community,

the ornate spoons featured an image of a trolley along with the name

"Brookline."

A few of these spoons, now over a century

old, have survived the test of time, like the one shown here. These spoons were

the very first commemorative Brookline souvenirs ever offered, and a prized piece

of our community's streetcar heritage.

The Brookline Herald was a Pittsburgh Press

insert that ran for a few weeks in October 1907. The Herald ran a small contest in

the October 20 issue, and some of the prizes offered were commemorative spoons

like the one shown above.

The contest winners were published in the

October 27 issue. Both editions are shown below. Could the spoon shown above have

been one of those lucky spoons?

The October 27 issue of the Herald also reminds

readers that Brookline is only fifteen minutes from downtown Pittsburgh via the

transit tunnel, and the new high-speed electric railway will cut that time in

half. What an excellent reason to invest in Brookline!

Digging Up The

Past - 2014

Beginning in February 2013, Brookline

Boulevard was the site of a seventeen month reconstruction and renovation effort. The project included infrastructure improvements

like new sidewalks, overhead lighting and signage. The highlight of the project

was the repaving of Brookline Boulevard from Starkamp Avenue to Pioneer

Avenue.

Although, in the end, the reconstruction

effort unveiled a picturesque new boulevard, the process of getting to that point

was a difficult and frustrating experience for the merchants and

motorists.

Work was halted in November due to the

onset of winter, and by the spring of 2014 the cold months had taken quite a

destructive toll on the boulevard. Enormous potholes turned the road surface

into a veritable moonscape. Mastery in the Art of Pothole Dodging has become

a pre-requisite to anyone brave enough to run the gauntlet.

In the midst of this urban chaos

came one award-winning pothole. The old-school strut-shocker was

spotted on April 7, 2014. It wasn't the size that made it stand out. Although

it was large, it paled in comparison to some of the truly abyss-like crevices

nearby.

Brookline Boulevard's Pothole to the

Past.

What gave this pothole character was

the old red paving brick road surface and the trolley track. This historic

part of Brookline Boulevard has been in place since the early 1900s. In 1966,

when the trolley line was discontinued, it was paved over in asphalt.

Forty-seven years and five inches of

asphalt later, the forces of nature, accompanied by liberal amounts of rock

salt, brought this bygone part of Brookline Boulevard back into the light of

day, if only for a few days. The following day it was paved over with cold

patch.

The old bricks and tracks were

brought back to the surface in June 2014.

In June of 2014 the reconstruction

project reached it's final phase, and the roadway was completely milled down

to the bricks, exposing the complete length of the trolley tracks that ran down

the center of the boulevard. Once again, the old red bricks and tracks were

exposed.

After this brief glimpse back to the

glory days of Brookline's transit history, the paving company out a fresh layer

of asphalt on the boulevard and, just like that, the tracks were once again

buried. It may take another fifty years before they see the light of

day.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><>

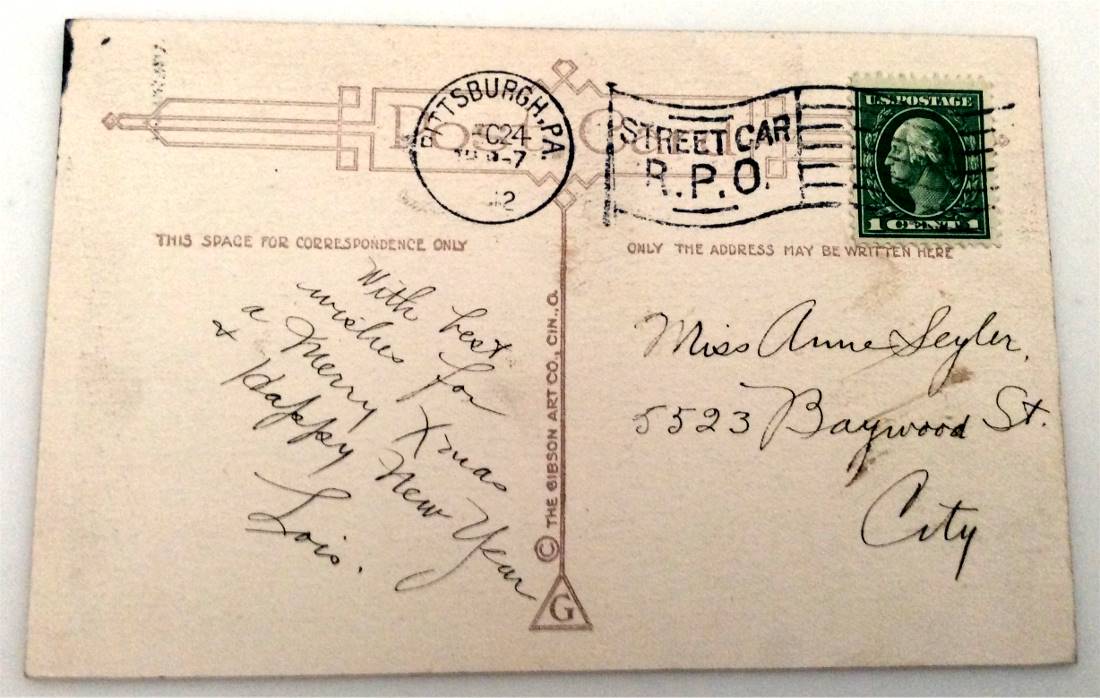

During the early 1900s, the U.S. Post Office

Department operated Railway Post Offices (RPOs) on streetcars in several cities,

including Pittsburgh, to carry mail between post office branches. Postal clerks were

stationed aboard the cars to sort the mail and speed processing at the post offices.

Some interurban routes also served as RPOs.

People could deposit mail on these cars,

sometimes via slots in their sides. The clerks would postmark that mail on the spot

while the car rolled. Shown here is an example of one such postcard with a Pittsburgh

Streetcar RPO cancellation stamp postmarked Dec 24, 1912, that was found in an old

scrapbook by former Brookline resident Bill Mullen.

It is unknown if a Railway Post Office

was ever attached to the 39-Brookline route, but the postcard above is an

interesting sliver of Pittsburgh Railways history.

There was a time when conductors would issue

change for fares. Streetcars were equipped with a standard coin dispenser and transfer

holder. The policy of conductor's carrying loose change ended in 1968.

A couple years ago, Jeff Wilinski called

to say he'd come across this streetcar passenger counter in an old box when preparing

to move. It still worked, and rather than throw it away he donated it to the

Brookline Historical Society. It's just another example of the many places where

we can find our hidden past. Let's dig it up, folks.

Models Of The 39-Brookline

And South Hills Junction

A replica of the 39-Brookline trolley made

by Dr. Michael Brendel.

A model layout of the South Hills Junction

by Bob Dietrich. For more Junction model photos, click here.

We are always looking for old

photos and information on trolleys in Brookline.

If you have something to share, please contact us via our guestbook.

* Compiled from

various sources, including the Press and Post Gazette - Last Updated: April 20, 2015 *

* Several of the Brookline trolley photos are from the collections of Tom Castriodale

and George Gula *

A Short History

On Trolley Service In The City Of Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh's trolley history dates

to the 1850s when the State Legislature passed a law allowing "motor power

companies" to operate passenger railways by cable, electrical or other means.

The first passenger service was a horse-drawn trolley that operated in East

Liberty in 1859. Since then, the city has been at the forefront

of trolley transportation.

A cable trolley in Allentown (left) and

a horse-drawn trolley on Warrington Avenue in 1859.

JUNE 1887: Pittsburgh Traction Company

constructs a cable line beginning at the foot of Fifth Avenue and running east

along Shady, Penn and Highland Avenues, a distance of 5.5 miles. The line

opens for passengers on September 12, 1889. Various cable lines operate in the

City of Pittsburgh until 1897.

THE LATE 1890's: The first

electric line is constructed from South 13th and Carson streets to

Knoxville Borough. That is followed by development of successful and

consistent electric trolley service on the North Side and the South Side.

In the ensuing years, competing lines are built by 190 trolley operators

in the city. The wooden trolley cars have four wheels.

A Pittsburgh Traction Company

cable line loop, located at

Fifth and Liberty Avenues in 1890.

"It was really a hodgepodge," says

Scott Becker, executive director of the Pennsylvania Trolley Museum in

Washington, near the Meadowlands.

JUNE 1901: Pennsylvania's Focht-Emery

Transit Bills are signed into law, opening a rush of investors wishing to

form new transit companies throughout the region to compete with the established

passenger railways. The sweeping domain and financial powers granted under the

new legislation fuel the expansion and modernization of Pittsburgh's public

transportation system. The bills also led to rampant stock fraud.

JANUARY 1, 1902: Pittsburgh Railways Company, a subsidiary of the Philadelphia Company, is

formed on June 8, 1901 as a result of the transit bills to consolidate the

increasing number of transit companies in Allegheny County. There are 1100

trolleys in operation along 400 miles of single track. Yearly ridership totals

178.7 million passengers with revenue of $6.7 million.

The first generation electrified traction

cars were wooden cars covered in steel-sheeting, sometimes referred to as "box cars."

They were built by the St. Louis Car Company at a cost of $6000 each and introduced

in Pittsburgh during the winter of 1902.

The eight-wheelers were forty-seven feet long

and powered by four fifty-horse power motors. The cars had high floors, narrow doors

and sat forty-four passengers on wooden seats. They could be driven from either side

of the vehicle by moving directional controls and electrical guide wire from one end

to the other.

DECEMBER 1, 1904: The Mount Washington Transit Tunnel a 3,500 foot bore through Mount Washington, opens

to traffic. The tunnel, from the South Hills Junction to Carson Street, was built

at a cost of $875,000. The inner walls were lined with 12,000,000 bricks. This

tunnel, along with the Corliss Tunnel (1914) on the West End, led to real estate

booms in both the South Hills and Sheridan areas, respectively.

A Philadelphia Company executive called it

"one of the greatest works ever undertaken in the street railway business. The

project will be the making of the South Hills." He was correct. In a span of just

one year, three farms in Brookline increased in valuation from $68,000 to $1.3

million.

The standard turn-of-the-century

streetcar has eight wheels, high steps and narrow doors. This makes traveling

slow and cumbersome, particularly for women whose clothes don't allow them

to negotiate the cars.

A 1905 Freehold Real Estate advertisement

that shows the new trolley line running to Brookline.

OCTOBER 1906: Company records indicate

that there are over 280 subsidiary companies either owned or leased by Pittsburgh

Railways.

1912: Pittsburgh's trolley network

is growing fast and the number of passengers increasing. Because of the

over-crowded conditions during peak times, P. N. Jones, head of Pittsburgh

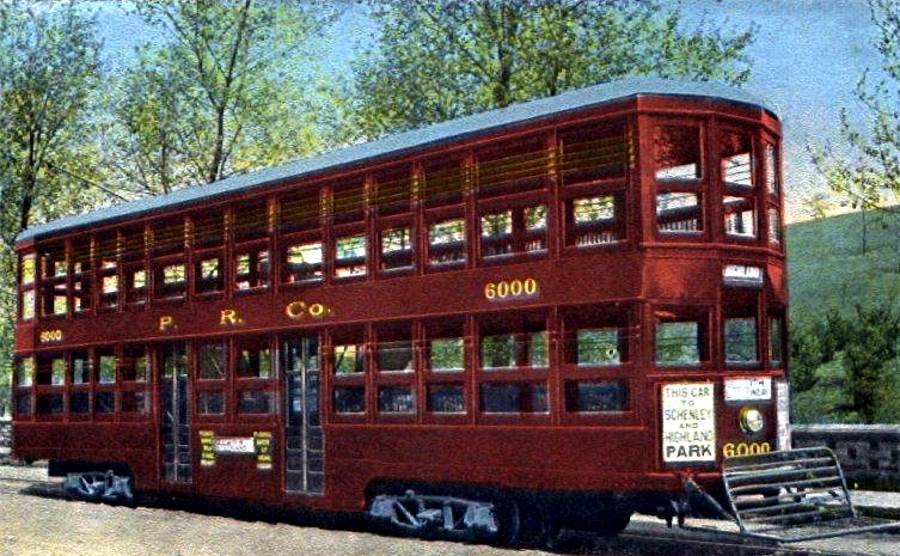

Railways, leads the effort to produce a standard car. The city tries out

double-decker cars. About a dozen were built between 1912 and 1924, but

they never really catch on in Pittsburgh.

1915: Pittsburgh Railways decides

that the new, low-floor Jones Car, built in McKees Rocks, with its sloping

floor is going to be its standard car. The company purchases 1000 of them

between 1915 and 1927. The steel cars run on 600 volts of direct current

and feature rattan seats, beautiful woodwork, windows that open and shaded

light bulbs. The cars are well-received by the public.

The trolleys are painted orange

but their color fades to yellow, prompting most people to call them

yellow trolleys. They are used in Pittsburgh until the mid-1950s, when

many trolleys are phased out in favor of buses.

Pittsburgh Railways

Double-Decker.

In the ensuing years, Pittsburgh

Railways experimented readily with a variety of cars, testing aluminum,

fiddling with control systems and trying a number of options with

wheels.

1918 - The Pittsburgh Railways Company

files for bankruptcy. Negotiations with the City of Pittsburgh drag on for

six years. Valued at $62.5 million, the companies credit obligations are

settled and a city Board of Advisors appointed to oversea the company

management. The Pittsburgh Railways Agreement goes into effect in April

1924 to keep the streetcars rolling.

An outbound Dormont streetcar on West Liberty

Avenue, passing the southern end of Pioneer Avenue in 1918.

Long-time Pittsburgh Railways conductor

Owen Richard McCaffrey Sr. of Overbrook, pictured in the early 1920s.

1926: Pittsburgh

Railways operates 590 miles of single track; carries 396,679,675

passengers a year and has revenue of $21.7 million.

1928: Pittsburgh Railways begins

producing high speed trolleys for its interurban lines that run to Washington

and Charleroi. The company makes fifteen cars that are painted red and feature

bucket seats.

Portions of the Charleroi Short Line remained

in service until September 4, 1999 as the Port Authority's "Library" Light Rail

Transit line. A portion of the Washington line survived as the "Drake" or Overbrook

line, service that ended in the late-80s and began again in 2004.

THE 1930s: Pittsburgh, like the

country, is in the depths of the Depression. Pittsburgh Railway is losing

ridership, but the company does not lose its tradition of supporting

innovation. The company is enthusiastic about the ideas for a new car

being developed at the request of the American Electric Railway

Association Advisory Council.

The plan for the car's development is

overseen by the Electric Railway Presidents Conference Committee, which

turns to Pittsburgh's Westinghouse Company for help designing the

revolutionary new car.

JULY 26, 1936: The first

Presidential Conference Committee car, # 100, goes into service in the

city. Pittsburgh Railways, trying to lure Depression-weary riders back to

the trolleys, promotes the car in newspaper advertisements and on

sandwich boards and with demonstration rides. Car #100 becomes the first PCC

car to carry passengers for a fare on September 26, 1936, when it covered

the 50-Carson Street Route.

FEBRUARY 4, 1937: The first 100 PCC

enter the Pittsburgh fleet. The new cars were used on the 38-Mt. Lebanon

route.

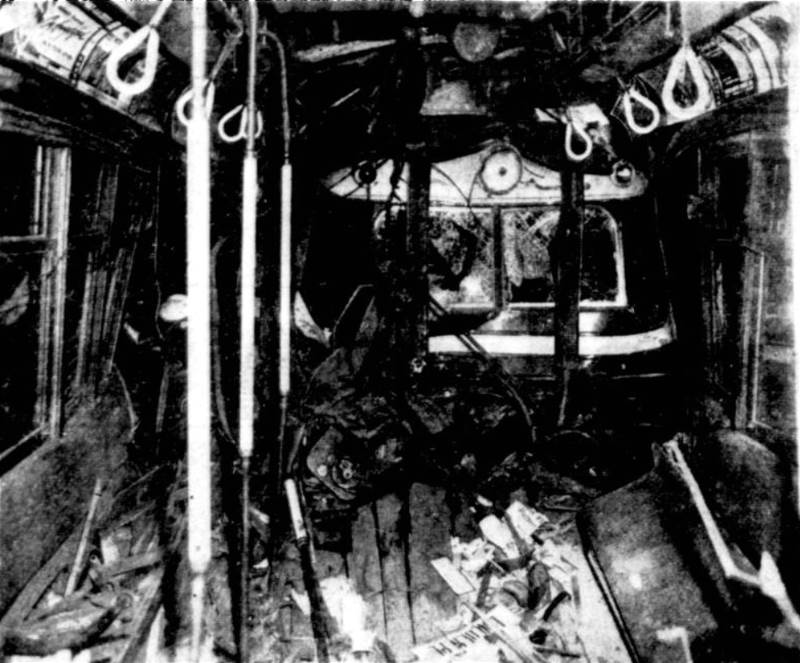

The inside of a PCC car, looking

towards both the front and rear.

Over the next twelve years, Pittsburgh

Railways orders 666 of the cars, at a cost of $28,000 apiece, from the St. Louis

Car Company to replace the oldest trolleys in the fleet, which still included

several of the original 1902 model high-floor trolleys. The new PCC streetcars

were painted in a red and cream color scheme.

1938: The financially struggling

Pittsburgh Railways Company files for bankruptcy. The reorganization effort

between the transit agency and the City of Pittsburgh drags on for thirteen

long years.

The first inbound trolley to use the

West Liberty Avenue trolley ramp was photographed on August 15, 1939.

1939: Due to the growing vehicular

congestion at the busy intersection of West Liberty Avenue and Saw

Mill Run Boulevard, a new trolley ramp was constructed along the lower end of West

Liberty Avenue. This diverted the 39-Brookline and 38-Mount Lebanon trolleys

from the crowded junction and on to the line used by Dormont and Beechview

trolleys.

The cost of the new ramp was $347,000.

It opened to traffic in August 1939. The Brookline and Mount Lebanon trolleys

now used the West Liberty ramp to connect to the Palm Garden Trestle on their

way towards the South Hills Junction.

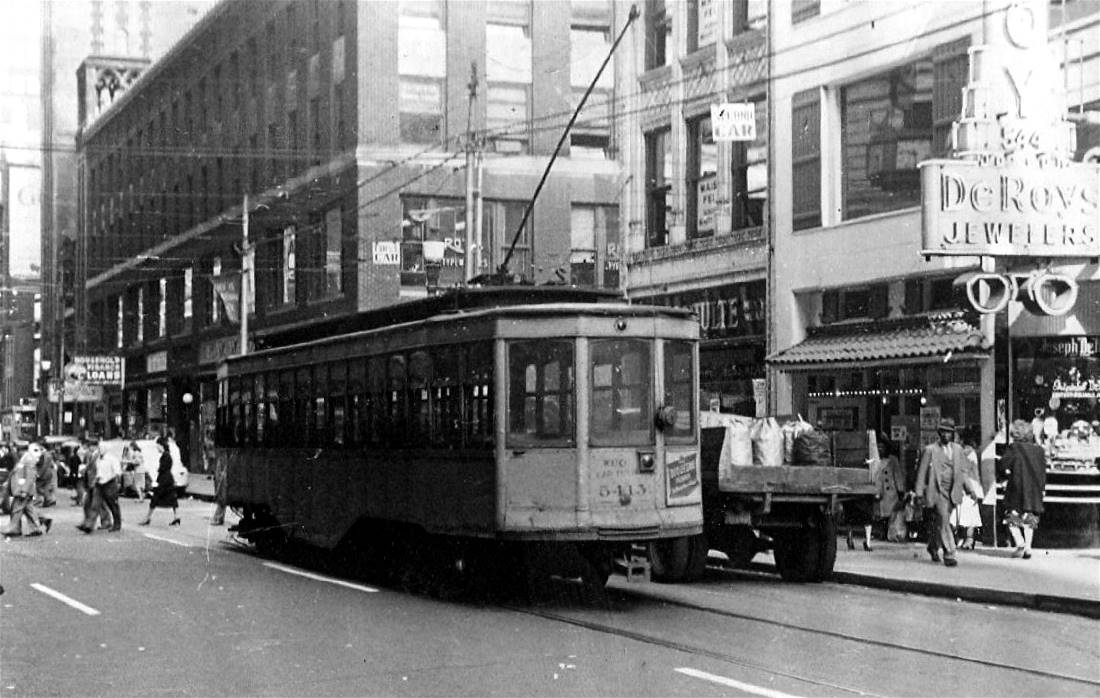

One of Pittsburgh Railways "Jones Cars"

downtown on Smithfield Street (circa 1945).

APRIL 2, 1940 - Pittsburgh Railways

receives a shipment of 100 new cars from the St. Louis Car Company, bringing

the fleet total to 301, the largest single fleet in the nation. Seventy-two

of the new cars were equipped with the latest Westinghouse motor and braking

systems. The cars enter continual service for the first time on the 39-Brookline

and 42-Dormont/Beechview routes.

1949: The Pittsburgh Railways PCC trolley

fleet is the 2nd largest in the country. Only Chicago, which operates 683 cars,

is bigger.

JANUARY 1951: Pittsburgh Railways, the

City of Pittsburgh and Allegheny County reach an agreement to end the thirteen

year company reorganization. The cars keep rolling, but changes in public

transportation will soon threaten the existence of the mighty

rail network.

SUMMER, 1953: Interurban trolley service,

which had boomed during the World War II and Korean War years, is scaled back to

the border of Allegheny County.

Map of South Hills Trolley

Lines.

MARCH, 1964: The Port Authority of

Allegheny County is formed to unify all public transit services. Despite the

declining trolley use, the authority inherits the Pittsburgh Railways fleet

of 283 PCC trolley cars and 219 buses.

1964 to 1967: Many rail routes are

converted to bus routes, including the 38-Mount Lebanon and the 39-Brookline

route, which made its final run on September 3, 1966.

1968: The Port Authority is

operating fifty-eight miles of track, only ten percent of the

Pittsburgh Railways network that was in operation forty years

earlier.

Many South Hills lines were replaced with

bus service, including 38-Mt.Lebanon and 39-Brookline.

The rails and passenger kiosks along West Liberty Avenue were

removed.

1972: The ninety-five remaining

PCC cars servicing the South Hills get new paint jobs, including one with

a psychedelic look.

LATE-1970s: An attractive feature that

was introduced at the time was a new advertising scheme. Trolleys could be

corporate sponsored and decorated at will. Soon, many of Pittsburgh's trolleys

took on a new look. Some of the memorable designs that stood out were

the Pittsburgh Steeler's Terrible Trolley, the Bicentennial Spirit of America,

the Clark Bar and the Gateway Clipper Triple Treat.

1981: The Port Authority plans to

refurbish forty-five PCC trolleys for use on the city's new "T" Light Rail

System. The $763,000 cost is prohibitive and only twelve are completed

before the program is abandoned in 1987.

JULY 3, 1985: Trolley street

operations in the Golden Triangle cease when the downtown subway, part of

the Light Rail "T" System, is opened. All above ground tracks in

downtown Pittsburgh are eventually removed or paved over.

The only rail routes that remain

in operation are part of the new Light Rail System. They are the

Beechview/South Hills Village line, the Warrington/Arlington line and the

Library extension. Soon, the only route still using the aging PCC trolley

cars was the Library line.

A PCC trolley at the Wood Street

Subway Station in 1985.

AUGUST 1, 1988: thirty-six PCC cars

are removed from operation because of deteriorated electrical wires.

Twenty-seven of those are retired and used to supply parts for the few

that remained in operation along the Library line.

SEPTEMBER 4, 1999: The final PCC

car makes the 4.4 mile Library extension run before the route was retired

forever, being replaced by a shuttle bus. The three remaining functional

PCC cars, all having logged well over 2,000,000 miles, were donated to

trolley museums.

A PCC car stands outside

the trolley museum in 2007.

JANUARY 2000: Pittsburgh no longer has

hundreds of miles of trolley track lining the streets, but the city still boasts

a state-of-the-art Light Rail system servicing the downtown area and South

Hills, including Beechview, Dormont, Warrington Avenue/Arlington Heights,

Castle Shannon, Bethel Park and Library.

JUNE 2004: The Port Authority

completes the four-year reconstruction the old Shannon Drake line, bringing